Historical background

Like all professions and aspiring professions, management has evolved as the result of a combination of accidents, piecemeal and isolated incidents and initiatives, together with lucky discoveries, pioneering and targeted activities, expert research and pioneering ventures. Management has had to respond to public, economic and environmental demands, and the pressures placed by politicians, financial interests and social and legal changes. Management has had to come to terms with industrial, social and technological revolutions, and to become and remain effective in response to the constraints and opportunities offered by each. Above all, management is a human activity, requiring a strong identity and affinity with the people who make up the stakeholder bodies – customers, suppliers, staff and backers, as well as vested interests, experts and commentators.

For certain, management is not yet a ‘profession’ in the terms in which this status and understanding is accorded to the law, the clergy or medicine. There is no agreed body of knowledge, understanding or expertise for management, though this is in the clear process of development. The vast majority of managers are not self regulating; indeed the main professional bodies of management have little statutory influence, though they do seek de facto to set the highest possible standards for their members. However, the ever greater pressures to ‘perform’ (whatever that means), to use resources effectively, and to deliver performance from others, does mean that a ‘professional’ approach is increasingly being sought and demanded – and this requires full knowledge and understanding of where the historic and current lessons come from, and what was learned from them.

The points that follow are some of the main landmarks of which all students of management and practising managers should be aware. The text here was originally produced in detail for the third edition of this book; it has been edited and mended in order to ensure that it is fully up to date, and that it delivers the lessons in the present context.

Marxism

The ferment of ideas that ran concurrently with the industrial and social upheaval brought with it the concept of communism. Written and developed by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, the Communist Manifesto propounded that industrial society as it stood was to be a place of permanent upheaval and revolution; that the workers, the wage slaves, would not tolerate the current state of industrial society, but would rather overthrow it and seize control of it for themselves. Egalitarian in concept, it rejected the then emerging concepts of capitalism, bourgeoisie (the middle and professional classes), and the fledgling wage-work bargain. Largely discredited as a philosophy (above all by the collapse of the communist bloc that called itself Marxist), Marxism never succeeded in translation into an effective code for the organisation of work. However, it does illustrate the extreme or radical perspective on working situations; the extent to which the workforce may become alienated either from the organisation for which they work or from its managers. It also voices genuine concerns for the standards, dignity and rights of those who work for others in the pursuit of supporting their own lives. It became the cornerstone of the trade union movement in the UK and elsewhere. The attraction lay in the egalitarianism preached and the utopian vision of shared ownership of the means of production and economic activity.

Example 1: Marxism and Egalitarianism

Paradoxically, at exactly the time when Marxism is discredited as a political and social philosophy, it is possible to identify more clearly a direct link between economic prosperity, organisational longevity, and high levels of organisational staff output and quality. For example:

- Lincoln Electric: which makes manufacturing, welding and electronic equipment for the American ship and automobile industries, has paid out extensive bonuses to all staff, based on a combination of suggestions received and organisational profitability, since 1932. The result of this has been that the company has not had a single lay-off since that date, and that the staff regularly earn, in productivity and performance-related bonuses, approximately double their income.

- Semco: the Brazilian manufacturing and internet corporation, always makes over 23% of gross profits for distribution among the staff.

- Nissan UK: based at Washington, Tyne and Wear, consistently achieves the highest levels of productivity of any car company anywhere in the world (with the exception of one factory in Japan and one in Korea), and this is founded in the adoption of, and commitment to, single staff status for all those working for the company.

Bureaucracy and the permanence of organisations

Weber (1864-1920) developed the concept of the permanence and continuity of organisations. This was the basis of the theory of bureaucracy. Weber saw bureaucracy as an organisational form based on a hierarchy of offices and systems of rules and with the purpose of ensuring the permanence of the organisation, even though jobholders within it might come and go. The knowledge, practice and experience of the organisation would be preserved in files, thus ensuring permanence and continuity. Authority in such circumstances is described as legal-rational, where the position of the office holder is enshrined in an organisation structure and fully understood and accepted by all jobholders. The organisation itself is continuous and permanent. Work is specialised and defined by job title and job description. The organisation is hierarchical, where one level is subject to control by that or those above it. Everything that is done in the name of the organisation and its officials is recorded. Jobholders are appointed on the basis of technical competence; the jobs exist in their own right; jobholders have no other rights to the job. Ownership and control of the organisation are separated; effectively the owners of an organisation appoint others to run it on their behalf. The work and the control of it is enshrined in rulebooks and procedures which must be obeyed and followed. Order and efficiency are thus brought to this state of permanence.

Thus, the overall purpose of bureaucratic structure was, and remains, to attain the maximum degree of efficiency possible and to ensure the permanence of the organisation. As organisations grow in size and complexity, the bureaucracy itself has to be managed. Failure to do this leads to red tape, excessive procedures, obscure and conflicting rules and regulations. In the worst cases, the rules and procedures become themselves all-important to the detriment of the product or service that is being offered.

The origins of welfarism

The Cadbury family who pioneered and built up the chocolate and cocoa industries in Great Britain in the nineteenth century came from a strong religious tradition (they were Quakers). Determined to be both profitable and ethical, they sought to ensure certain standards of living and quality of life for those who worked for them. They built both their factories and the housing for their staff as a model industrial village at Bourneville on the (then) edge of Birmingham. The village included basic housing and sanitation, green spaces, schools for the children and company shops that sold food of a good quality. The purpose was to ensure that the staff were kept fit, healthy and motivated to work in the chocolate factories, producing good quality products. Other Quaker foundations operated along similar lines, for example the Fry and Terry companies (which also produced chocolate). Similar attitudes may also be found at the present time at, for example:

- Body Shop: where all staff are required to work one day per month on the social or environmental project or activity of their choice (see continuous case study in the main text)

- Sony UK: where there is a commitment to lifetime employment as above, and guarantee of no compulsory redundancies (though the company is at present struggling to deliver this commitment in its western operations)

More generally, many organisations have sought to balance the quality of working life and commitment of their staff, by introducing flexible working (which must now be offered by law if requested), private healthcare insurance and crèche and nursery facilities (examples include British Airways, British Telecom, Citibank).

This was by no means the rule, though it was considered a commitment by the new middle classes of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, who saw their role as contributing to overall prosperity as well as their own. Nevertheless, many employers continued to treat their people very harshly, keeping them in bad conditions, under-paying them and using fear as the driving force. Graphic and apocryphal descriptions may be found in the poetry of William Blake, and The Water Babies by Charles Kingsley. However, the work of the Cadburys and the others is important as one of the most enduring early industrial examples of the relationship between concern for the staff and commercial permanence, profitability and success. And most of the above companies exist to this day; while most of those that sought to profit from poor conditions do not.

Henri Fayol

The work of Henri Fayol (1841-1925) is important because he was the first to attempt a fully comprehensive definition of industrial management. This was published in 1916 under the title General and Industrial Administration. It identified the components of any industrial undertaking under the headings of technical; commercial; financial; security; accounting; and managerial. This last group of components comprised forecasting, planning, organisation, command, coordination and control of the others; the overall function is to unify and direct the organisation and its resources in productive activities. He also listed 14 'principles of management' on which he claimed to have based his own managerial practice and style and which he cited as the foundation of his own success:

- Division of work, the ordering and specialisation of tasks and jobs necessary for greater efficiency and ease of control.

- Authority and responsibility, the right to give commands and the acceptance of the consequences of giving those commands.

- Unity of command, each employee has an identified and recognised superior or commander.

- Unity of direction, one commander for each activity or objective.

- The subordination of individual interests to the organisational interest.

- Remuneration and reward in a fair and equitable manner to all.

- Centralisation and centrality of control.

- A discernible top-to-bottom line of authority.

- Order as a principle of organisation, the arrangement and coordination of activities.

- Equity, the principle of dealing fairly with everybody who works for the organisation.

- Employee discipline, ensuring that everybody receives the same standard of treatment at the organisation.

- Stability of job tenure, by which all employees should be given continuity of employment in the interests of building up expertise.

- Encouragement of initiative on the part of everyone who works in the organisation.

- Esprit de corps, the generation of organisation, team and group identity, willingness and motivation to work.

Fayol's work stands as the first attempt to produce a theory of management and set of management principles. Fayol also recognised that these principles did not constitute an end in themselves; that their emphasis would vary between situations; and that they would require interpretation and application on the part of those managing the situation.

Scientific management

The concept of scientific management, or the taking of a precise approach to the problems of work and work organisation, was pioneered by Frederick Winslow Taylor (1856-1917). His hypothesis was based on the premise that the proper organisation of the workforce and work methods would improve efficiency. It was based on the experience of his career in the US steel industry. He propounded a mental and attitudinal revolution on the part of both managers and workers. Work should be a cooperative effort between managers and workers. Work organisation should be such that it removed all responsibility from the workers, leaving them only with their particular task. By specialising and training in this task, the individual worker would become 'perfect' in his job performance; work could thus be organised into production lines and items produced efficiently, and to a constant standard, as a result. Precise performance standards would be predetermined by job observation and analysis and a best method arrived at; this would become the normal way of working. Everyone would benefit - the organisation because it cut out all wasteful and inefficient use of resources; managers because they had a known standard of work to set and observe; and workers because they would always do the job the same way. Everyone would benefit financially also from the increase in output, sales and profits, and the reflection of this in high wage and salary levels. In a famous innovation at the Bethlehem Steel Works, USA, where he also worked, Taylor optimised productive labour at the ore and coal stockpiles by providing various sizes of shovels from which the men could choose to ensure that they used that which was best suited to them. He reduced handling costs per tonne by a half over a three-year period. He also reduced the size of the workforce required to do this from 400 to 140.

Example 2: Scientific Management Criticised

The great weakness of the scientific management approach is that it took no account of the human and social needs of those working in these conditions. Taylor reasoned that by guaranteeing high levels of pay, satisfaction would automatically follow.

This has consistently been shown not to be the case. For example:

.

- The UK coal mining industry lost 400,000 jobs between the years 1975-1995. The miners were among the best paid workers in the UK. Despite exhortations from their trade union, when the miners were offered redundancy payments, the vast majority took them - again, because they were treated as a disposable commodity, rather than human beings.

- Those going to work in Dot.com companies in the late twentieth century did so in the belief that they were part of a new industrial revolution. They quickly discovered that, apart from the chosen few who owned the companies, they were to be required to work in cubicles, in front of computer screens, for long periods of time. The directors of Dot.com companies quickly discovered that, in contrast to their own zeal and enthusiasm, their staff were unwilling to be treated in this way.

The great advances that Taylor and those that also followed the scientific school made were in the standardisation of work, the ability to put concepts of productivity and efficiency into practice. The work foreshadowed the production line and other standardised and automated efforts and techniques that have been used for mass-produced goods and commodities ever since. In the pursuit of this, scientific management also helped create the boredom, disaffection and alienation of the workforces producing these goods that still remain as issues to be addressed and resolved into the 21 st century (see Summary Box 1.2).

The human relations school

The most famous and pioneering work carried out in the field of human relations management was the Hawthorne Studies at The Western Electric Company in Chicago. These studies were carried out over the period 1924-1936. Originally designed to draw conclusions between the working environment and work output they finished as major studies of work groups, social factors and employee attitudes and values, and the effect of these at the place of work.

The Hawthorne Works employed over 30,000 people at the time, making telephone equipment. Elton Mayo, Professor of Industrial Research at Harvard University, was called in to advise the company because there was both poor productivity and a high level of employee dissatisfaction.

The first of the experiments was based on the hypothesis that productivity would improve if working conditions were improved. The first stage was the improvement of the lighting for a group of female workers; to give a measure of validity to the results, a control group was established whose lighting was to remain consistent. However, the output of both groups improved and continued to improve whether the lighting was increased or decreased. The second stage extended the experiments to include rest pauses, variations in starting and finishing times, and variations in the timing and length of the lunch break. At each stage the output of both groups rose until the point at which the women in the experimental group complained that they had too many breaks and that their work rhythm was being disrupted. The third stage was a major attitude survey of over 20,000 of the company's employees. This was conducted over the period 1928-1930. The fourth and final stage consisted of observation in depth of both the informal and formal working groups in 1932. The final stage (1936) drew all threads together and resulted in the commencement of personnel counselling schemes and other staff related activities based on the overall conclusions drawn by Mayo and his team from Harvard and also the company's own researchers.

These may be summarised as follows.

- Individuals need to be given importance in their own right, and must also be seen as group or team members.

- The need to belong at the workplace is of fundamental importance, as critical in its own way as both pay and rewards and working conditions.

- There is both a formal and informal organisation, with formal and informal groups and structures; the informal exerts a strong influence over the formal.

- People respond positively to active involvement in work.

What started out as a survey of the working environment thus finished as the first major piece of research on the attitudes and values prevalent among those drawn together into working situations. The Hawthorne Studies gave rise to concepts of social man and human relations at the workplace. They were the first to place importance on them and to set concepts of groups, behaviour, personal value and identity in industrial and commercial situations.

Winning friends and influencing people

This work was carried out by Dale Carnegie in the early part of the twentieth century. He was a pioneer of some of the concepts that have now become part of the mainstream of good business and management practices.

Carnegie identified the barriers and blockages to profitable and effective activity. He summarised this as 'overcoming fears'. The starting point for nearly all transactions was having to deal with humans on a face-to-face basis as the prerequisite for commercial success.

To do this successfully he identified certain fundamental techniques for handling people. The main factor is empathy: the ability to put yourself in the other person's position, seeing things from their point of view, understanding their wants, needs, hopes and fears; and understanding what they want from the transaction (not your wonderful product per se, but rather the benefits that are expected to accrue). The customer is at the centre of the transaction and therefore, is entitled to feel important and to have their wants and needs attended to and satisfied.

Carnegie identified other characteristics in support of this that would reinforce the effective capabilities of anyone who deals with customers. These are: learning to take a genuine interest in people; the development of a positive persona; listening attentively and responding to the needs of the customers, encouraging them to talk; speaking in terms of their interests; and being sincere. Language used should always be positive and couched in terms that encourage progress and positive responses. Staff should never argue with customers.

More generally, Carnegie preached the value of positive rather than negative criticism - above all, when it is necessary to tell someone that they are wrong, sticking to the wrong deed rather than criticising their personality. The person in question should also be allowed to save face. Criticism should always be followed by constructive help and followed by an item of praise. In general, all people should be praised and valued, and given a high reputation - the organisation is going to need these qualities, and not those engendered by any lasting resentment.

Carnegie also preached the more general virtues of honesty, openness, self-respect, commitment and clarity of purpose as being central to business and commercial success. The lessons taught by Carnegie run throughout the whole of the philosophy of human relations and are to be found in the practices of many successful companies and those regarded as 'excellent'. The importance of, and central position of, 'the customer' is a feature current in the offerings of business schools in the last decade of the twentieth century, as well as being a critical factor in the successes of Japanese industry and commerce.

The 'Affluent Worker' studies

The affluent worker studies were carried out at Luton, UK, in the early 1960s. There were three companies studied, Vauxhall Cars, La Porte Chemicals, and Skefco Engineering. The stated purpose was to give an account of the attitudes and behaviour of a sample of affluent workers, male high wage earners at mass or flow companies; and to attempt to explain them. Both the firms and the area were considered highly profitable and prosperous.

The main findings were as follows. The job was overwhelmingly a means to an end on the part of the workforce, that of earning enough to support life away from the company. The affluent workers had little or no identity with the place of work or with their colleagues; this was especially true of those doing unskilled jobs.

Some skilled workers would discuss work issues and problems with colleagues. The unskilled would not. In general, the workforces felt no involvement with either the company, or their colleagues, or the work. Generally, positive attitudes towards the company prevailed, but again these were related to the instrumental approaches to employment adopted; the companies were expected both to increase in prosperity, and to provide increased wages and standards of living. The companies were perceived to be 'good employers' for similar reasons.

The matters to which the affluent workers were found to be actively hostile were those concerning supervision. The preferred style of supervision was described as 'hands off'; any more active supervision was perceived to be intrusive. Work study and efficiency drives were also opposed. There was a very high degree of trade union membership (87% overall), though few of the affluent workers became actively involved in either national or branch union activities. Union membership was perceived as an insurance policy. The main point of contact between workers and union was the shop steward who was expected to take an active interest, where necessary, in their concerns.

No association was found between job satisfaction and current employment. It was purely a 'wage-work bargain', a means to an end. The most important relationship in the life of the worker was that with his family. The workers did not generally socialise with each other, either at work or in the community; thus membership of workplace social clubs was also low.

The view of the future adopted was also instrumental. There was no general aspiration to supervisory positions especially for their intrinsic benefits. The affluent workers would rather have their own high wages than the status and responsibility of being the foreman. More generally, the future was regarded in terms of increased profitability and prosperity, an expectation that wages would grow and that standards of living and of life would, in consequence, grow with them.

The studies illustrated the sources and background of the attitudes and behaviour inherent in this instrumental view of employment. More generally, the studies concluded that levels of workplace satisfaction were conditional upon continued stability and prosperity; and that there were universal expectations of continuing growth in the situation.

The Peter Principle

Lawrence J. Peter worked as teacher, psychologist, counsellor and consultant in different parts of the American education sphere during the post-war era. This included education in prisons and dealing with emotionally disadvantaged and disturbed children.

The Peter Principle was published in 1969. It is based on the assumption and invariable actuality that people gain promotion to their level of incompetence - as long as they are successful in one job they will be considered a suitable candidate for the next by the organisation in question; and only when they are not successful in that job will they not be considered for the next promotion (see Summary Box 1.3). The book is written in an essentially racy and light-hearted way; the lessons to be learned are nevertheless extremely important.

Promotions are clearly being made on a false premise, that of competence in the current job rather than the competence required for the new one. It follows from this that assessments for promotion are fundamentally flawed, based on the wrongful appraisal of the wrong set of characteristics. More generally, what is 'sound performance' in one job may simply be identifiable on the basis that the individual is not actually doing any harm.

In the management sphere, the application of the 'Peter Principle' is only too universal. Time and again promotion to supervisory and management grades from within the ranks is based upon the operative's performance in those ranks rather than on any aptitude for supervision, management or direction. Organisations thus not only gain an incompetent or inadequate supervisor, they also lose a highly competent technician. This remains true for all walks of life - the best nurses do not per se make the best hospital directors; the best teachers do not make the best school heads; the best drivers do not make the best transport fleet managers.

Example 3: The Peter Principle

'The head's friends saw that the head was no use as a head, so they made her an inspector, to interfere with other heads. And when they found she wasn't much good even at that, they got her into Parliament, where she lived happily ever after.'

Source: C.S. Lewis, The Silver Chair (1953).

The lessons to be drawn from this may be summarised as the ability to identify genuine levels and requirements of performance and attributes required to carry them out, and to set criteria against which they can be measured accurately. People may then be placed in jobs that they can do, and for which they are best suited. Aptitude for promotion, or any other preferred job for that matter, can then be assessed on the basis of matching personal qualities with desired performance and organisational appointments made accordingly. Finally, the principle also has implications for growing and nurturing your own experts and managers and for succession and continuity planning.

Business policy and strategy

The importance of this as part of the field of the study of management was first fully developed by H.I. Ansoff, who postulated theories concerning both the totality of, and complexities of, organisational and operational strategy. This work was carried out in the 1950s and 1960s.

Ansoff's stance was based in the concern found among business managers of identifying rational and accurate ways in which organisations could both adjust to and also exploit changes in their environment. Such ways he described as:

- Traditional, micro-economic theories of the firm which, while taking full account of 'the organisation in its environment', took no account of either its operational or behavioural procedures and practices.

- The need to reconcile a range of decision classes - strategic, administrative and operational - in both the allocation of, and competition for, the organisation's resources, priority, time and attention.

- Transition, from one state to another due to changes in technology, markets, working practices, size or scale of the firm and its operations.

- The application of science and technology to the process of management which was ever-increasing at the time. This generated both interest and acceptance of more analytical approaches.

The work of Ansoff was pioneering in what was then recognised as a complex field of study, and one that offered great scope for research from both an academic point of view and also in the interest of the pursuit of profitable business.

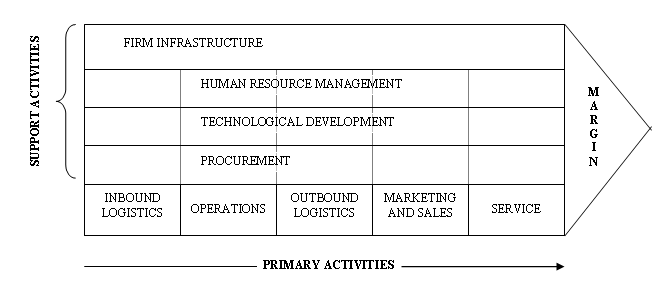

This work has been substantially developed by Michael E. Porter of the Harvard Business School, to include in depth analyses of strategy processes, competitive positioning and competitive advantage, developing and refining the key concepts outlined above and also delving much deeper into the complexities that constitute effective corporate strategies.

This has included substantial analyses of the interrelationships between organisations and their environment; and between each other in particular industrial and commercial sectors. In turn, he has related this to both the diversification and complexity of the organisations themselves that operate in particular spheres. He has isolated the concepts of defensive and offensive strategies and when each should be used. His work has produced a comprehensive set of tools, techniques and methods for the analysis of companies, industries, sectors and markets.

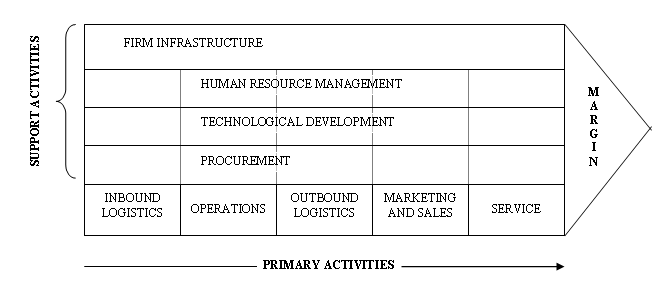

Porter's concept of the analysis of the 'value chain' (see Figure 1.1) identifies the elements that are critical in the devising and assessment of profitable or effective strategy, where the particular links in the chain lie, and the effect of each upon the whole of the strategy adopted. These links include:

- costs and their behaviour;

- the separation and combination of activities;

- the technology that is available and the ability of the organisation to use it;

- the identification of good and bad aspects of operations in the organisation and the market;

- the identification of good and bad industrial and commercial sectors and competitors within them.

These are then related both to the segments in which the organisation is to operate and the structures and sub-structures that it adopts in order to do this effectively.

Notes

The value chain breaks an organisation down into its component parts in order to understand the source of, and behaviour of, costs; and actual and potential sources of differentiation. It isolates and identifies the 'building blocks' by which an organisation creates an offering of value to its customers and clients:

- It is a tool for the general examination of an organisation's competitive position, and means of cost determination.

- It identifies the range and mix of characteristics necessary to design, produce, deliver and support its offerings.

- The value chain should be identified at 'business unit' level, for greatest possible clarity and accuracy.

Source: Michael E. Porter 1980, 1986

Figure 1.1 The Value Chain

Business and public policy and strategy is currently a major field of enquiry. This derives from the change, turmoil and turbulence that is present and endemic throughout the business sphere at present. As organisations get better at it, and understand the importance of conducting it and formulating it effectively, and in line with their own capabilities and capacities, they gain great advantages in their ability to compete in their chosen field.

Organisations, management and technology

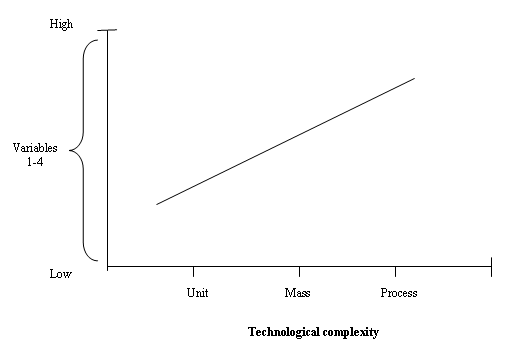

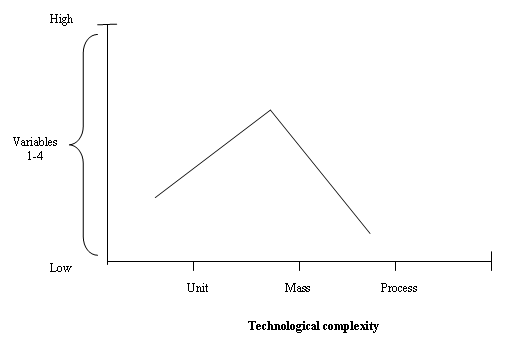

The relationships between the technology required to conduct certain industrial and production activities and the nature and style of organisation required to energise this was studied by Joan Woodward, who conducted research among the manufacturing firms of South East Essex in the post-war conditions of the 1950s.

1.

Variables:

- 1. Number of levels in management hierarchy

- 2. Ratio of managers and supervisors to total staff

- 3. Ratio of direct to indirect labour

- 4. Proportion of graduates among supervisory staff engaged in production

2.

Variables:

- 1. Span of total of first time supervisors

- 2. Organisation flexibility/inflexibility

- 3. Amount of written communication

- 4. Specialisation between functions of management, technical expertise; time-staff structure

Source: P.A. Lawrence (1985). Used with permission.

Figure 1.2 Organisations and Technology

The research looked at the organisational aspects of the levels and complexities of authority, hierarchy and spans of control in these organisations (see Figure 1.2). It also considered the nature and division of work - the clarity of the definition of jobs and duties, and the ways in which specialist and functional divisions were drawn. Finally, the nature of communications activities and systems in the organisations was analysed.

The conclusions drawn related the differences in these organisational aspects to the different technologies used in them. The technology was found to impinge on all factors - organisational objectives, lines of authority, roles and responsibilities and the structure of management committees. The nature, complexity and personality of systems for control were also found to be related to the technological processes in place.

The work also defined the levels of production process and complexity in technological terms that are now universally understood and used: those of unit production, batch production, mass production and flow production. It further developed the relationship between these and the nature and complexity of organisation required in each case, and above all, in regard to the highly capital, intensive mass and flow activities.

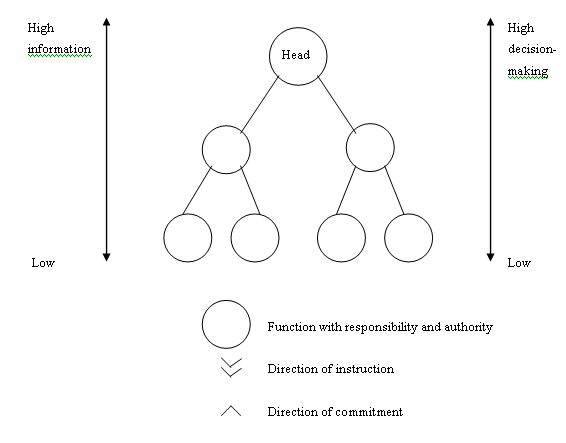

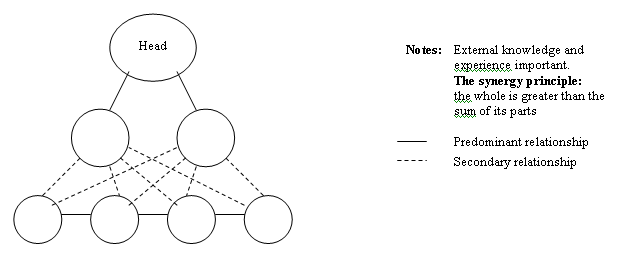

Socio-technical approaches: mechanistic and organic management systems

These model systems of management were proposed by T. Burns and G.M. Stalker in 'The Management of Innovation' (1966). The mechanistic system of organisation was found to be appropriate to conditions of relative stability. They are highly structured, and those working in them have rigorous formal job descriptions, clearly defined roles and precise positions in the hierarchies (see Figure 1.3). Direction of the organisation is handed down via the hierarchy from the top; and communication is similarly 'vertical'. The organisation insists on loyalty and obedience from its members, both to superior officers, and also to itself. Finally, it is the ability of the functionary to operate within the constraints of the organisation that is required.

Source: P.A. Lawrence (1985) (after Burns and Stalker).

Figure 1.3 Organisation Structures: Mechanistic

The organic model is suitable to unstable, turbulent and changing conditions. The organisation is constantly breaking new ground, addressing new problems, and meeting the unforeseen; and a highly specialised structure cannot accommodate this. What is required is fluidity, continual adjustment, task redefinition, and flexibility (see Figure 1.4).

Groups, departments and teams are constantly formed and reformed. Communication is at every level, and between every level. The means of control is regarded as a network rather than a personal commitment to it, that goes beyond the purely operational or functional.

Source: P.A. Lawrence (1985) (after Burns and Stalker).

Figure 1.4 Organisation Structures: Organic

Burns and Stalker develop their theme a stage further, to ascertain whether it was possible to move from the mechanistic to the organic. The conclusion was that they doubted that it could. When mechanistic organisations seek change, committee and working party systems are created and liaison officer posts are established. Additional stresses are placed on the existing structure and channels of communication of the organisation, compounding the difficulties and clouding the issues that are to be faced. The consequences are that progress tends to be stifled rather than facilitated.

Even more on historical background and overview:

Some enduring issues and priorities: