Are you sure you want to reset the form?

Your mail has been sent successfully

Are you sure you want to remove the alert?

Your session is about to expire! You will be signed out in

Do you wish to stay signed in?

The Charlton Comics Story

Charlton was already a successful publisher when it entered the comics market.

Charlton Comics was, in the words of comics scribe Tony Isabella, “the low-rent district of the comics industry.” Comic books were never more than a sideline for Charlton Publishing; a way to keep the expensive printing presses from sitting idle in-between runs of much more profitable magazines, such as Hit Parader and Song Hits. Most of the forty-one year publishing history of Charlton Comics was devoted to a steady production of derivative and unremarkable genre comic books.

In 1923, a 24-year-old John Santangelo left Italy to immigrate to the United States. Initially, he made his living as a bricklayer and masonry contractor. Then, in 1934, he came up with the idea of printing and selling the lyrics to the popular songs of the day. Soon he was making hundreds of dollars of supplemental income. According to the official history of the company, Santangelo was blissfully unaware that he was breaking copyright laws until his activities came to the attention of American Society of Composers, Authors and Producers. He was convicted of copyright infringement and sentenced to a year in the New Haven County jail. In jail he met white-collar criminal and former attorney Edward Levy. Levy recognized a good idea, and they formed a partnership to legally publish song lyric magazines. And because they both had infant sons named Charles, they christened their new venture Charlton Publishing. Their first publication was Hit Parader magazine in 1935, and it was published continuously until Charlton Publishing closed shop in 1991.

Levy and Santangelo’s entry into comic book publishing was tentative and convoluted. Some of their early titles did not last long and the name of the comic book publishing enterprise changed frequently. It was not uncommon for early comic book publishers to shuffle through a variety of company names to circumvent paper rationing and facilitate creative accounting. Whatever their motivation, Levy, as publisher, and Santangelo, as business manager, followed a similar practice. Their first comic book, the superhero and adventure anthology Yellowjacket Comics, appeared in 1944 as a publication of the Frank Comunale Publishing Company; Charlton Comics did not appear in the indicia until issue # 10. Toward the end of 1945 they introduced Zoo Funnies, the first five issues of which were published by Children’s Comics Publishers. A few one-shot titles in 1945 and 46 were published with either Special Action Comics or Charles Publishing Company as the publisher of record. By the summer of 1946 every title in their small stable of comics was being published by Charlton Comics, Inc. However, when Levy and Santangelo added crime and horror titles in the early 1950s a variety of publisher names (Law and Order Magazines, Outstanding Comics, Capitol Stories, and even Song Hits, Inc.) appeared in the indicia until they finally settled into using Charlton Comics Group in the mid-1950s.

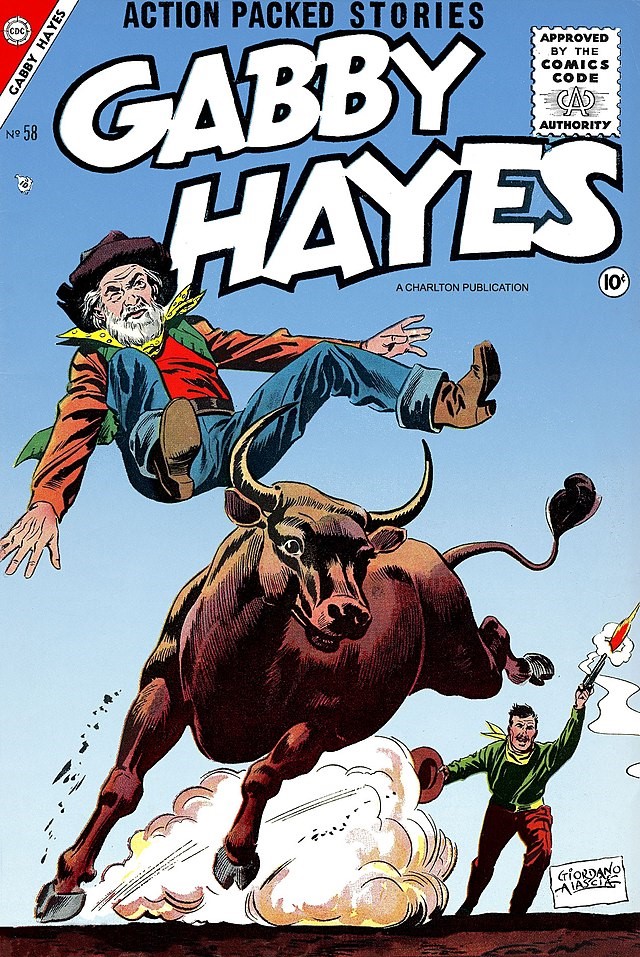

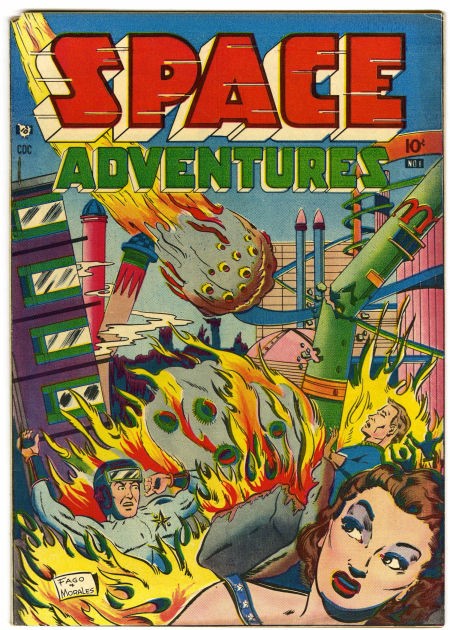

Funny animal, western, and romance books were the core of Charlton’s early comics publishing efforts, but they also followed the industry trends of the late 40s and early 50s with their own derivative crime (Racket Squad in Action), horror (The Thing), and science fiction (Space Adventures) comic books. For the next ten years Charlton was just one of the many small, unremarkable comic book publishers. Charlton Comics did not begin to thrive until the rest of the industry was in decline.

The comic book industry slump of the mid to late 1950s, brought on by distribution problems, parental concerns and competition from television, was a time of expansion for Charlton Comics. As other publishers went out of business or curtailed their production, Charlton aggressively acquired both characters and creators. Charlton Publishing had a number of advantages that helped it weather the hard times. Not only was there continued high demand for Charlton’s non-comics magazines, but Charlton Publishing was unique in that it was completely self-contained. Comic book scripts were written, pages were drawn, plates engraved and printed, and bundles of comic books were loaded on to trucks for distribution all out of the same huge building in Derby, Connecticut (although in later years comic book production was moved to a smaller nearby building).In the mid-1950s, Charlton acquired titles, mostly romance, western and horror, from a number of defunct publishers, including Fawcett Publications, Superior Comics, and Simon & Kirby’s Crestwood/Mainline Comics. The most significant acquisition was the Blue Beetle character from Fox Features Syndicate. Not that Charlton had much initial success with the character. After a brief run in Space Adventures in 1954, the Blue Beetle had his own title for four issues, three of which were reprints of Fox material. However, ownership of the name allowed Charlton to create an original Blue Beetle character as part of their 1960s emphasis on action heroes.

Charlton offered Captain Atom in response to the superhero revival of the early sixties. Noting the success of DC Comics’ superhero revivals in the late 50s, with updated versions of Golden Age characters such as Flash and Green Lantern, Charlton introduced a new superhero, Captain Atom, in 1960. When Dick Giordano took over as editor-in-chief in 1965 Charlton’s superhero era began in earnest. However, Giordano preferred to call Charlton’s costumed characters “action heroes” rather than superheroes. Aside from the incredibly powerful Captain Atom, the emphasis at Charlton was on costumed heroes without super-powers. In 1964 Charlton dusted off the Blue Beetle concept they had acquired from Fox, but by 1966 the character had been killed off and replaced by a Blue Beetle with no powers, but plenty of cool gadgets. Other notables in Charlton’s 1960s action hero line-up include The Question, Judomaster, The Fighting Five, and Peter Cannon – Thunderbolt. Most Charlton fans consider the high point of Charlton Comics history to be the action hero era during Dick Giordano’s 1965 to 1968 tenure as managing editor.

The Charlton comics line died by degrees. Overwhelmed by the popular DC superhero revivals and the innovative new line of Marvel superheroes, none of Charlton’s original action hero titles made it to the end of the 1960s (although many of the characters were briefly revived in the 1970’s). The appearance of E-Man in 1973 sparked some fan interest, but the title only lasted 10 issues. E-Man, an incredibly powerful energy being who could mold his body into any shape, was a departure from the action hero formula. His tongue-in-cheek adventures were reminiscent of Jack Cole’s Plastic Man from the 1940s. Like the new Blue Beetle in the previous decade, E-Man generated enthusiastic fan response, but disappointing sales. What success Charlton Comics did have in the 1970s came from its mild horror comics and licensed material such as Flash Gordon and The Phantom. The company stopped producing new comic book content in 1978 and began publishing reprint material from its vast inventory.

In 1983, for about $30,000 plus royalties, DC Executive Vice President Paul Levitz acquired the action hero titles as a gift for Dick Giordano, who by then had returned to DC. Then, after 40 years of steady but mostly mediocre production, Charlton Publishing closed their comic book publishing operation in 1985. The following year, the Charlton action heroes served as the template for Alan Moore and Dave Gibbon’s critically acclaimed Watchmen series.

In epitaph to the missed opportunities of the Charlton era, former editor-in-chief Dick Giordano said, “If they had wanted to go head-to-head with DC Comics, quality of the artwork, quality of the stories, quality of the printing and distribution, they probably could’ve done it at two-thirds the cost that DC was paying. And if they had done that, they really could have turned the comic book publishing business on its ear. But they chose to be junk dealers, they really did” (Cooke 2000, 34).

Bibliography

Cooke, Jon B. “The Action Hero Man: The Great Giordano Talks Candidly about Charlton.” Comic Book Artist 9 (2000): 30-51, 109.

© 2023 The Power of Comics and Graphic Novels