Are you sure you want to reset the form?

Your mail has been sent successfully

Are you sure you want to remove the alert?

Your session is about to expire! You will be signed out in

Do you wish to stay signed in?

Linguistics: An Introduction > Student Resources > Chapter 3

The tables on this page can be downloaded here:

3.1 Some difficulties with the notion of the morpheme

It is not all plain sailing with the notion of the morpheme. One difficulty is mentioned in the textbook (p.72), namely the problem of zero morphemes. It is useful to recognize these morphemes in certain cases, as they can provide a way to formulate morphological generalizations that would be otherwise impossible, as discussed for the Hungarian verb in the textbook (pp.71‒72). These have an identifiable meaning but no actual perceivable form. This is somewhat problematic for the idea of the morpheme as a Saussurean sign, since the signifier actually has no phonological form.

Other difficulties also exist. Here are a few:

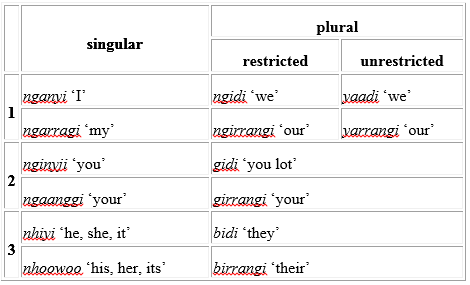

1. Lack of consistency in the contrasting forms In the examples discussed in the text, there is considerable consistency in the patterning of the forms of the morphemes in paradigmatic contrast, allowing you to identify a possible form for the morpheme. There may as well be some irregularities that do not follow this pattern, as in the case of the noun plural morpheme of English (e.g. the irregularity for ox). But sometimes no pattern is sufficiently recurrent to allow you to identify it as the regular pattern. Consider the forms of the pronouns of Gooniyandi, where two different case forms are shown, one for subject and object, the other for possessive (don’t worry about the meanings of restricted and unrestricted, this is irrelevant to our concerns here):

Although there are some regularities (e.g. plural number is marked by -di in the first row of forms, and by -rra in the second row), it is not possible to divide the pronouns easily into morphemes so that each can be described consistently in a formula such as we discussed in §3.6. (Try it!) And just four of the seven (a little over a half) of the possessive forms are formed by a pattern from the other forms. (How would you describe the pattern.) Trying to describe these forms in the way described in Chapter 3 is going to give us more exceptions than general patterns.

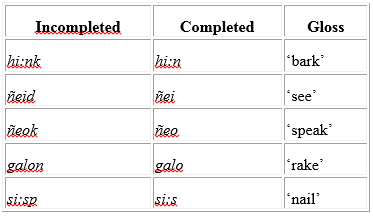

2. The identifiable pattern is the removal of phonological forms. Consider the following data from Tohono O’odham (Uto-Aztecan, Arizona USA):

If you try to identify a morpheme for Incompleted, notice that for the five words there would be four different forms for it. On the other hand, notice that the Completed forms are regularly formed from the Incompleted forms by removing the final consonant. In this case, you loose generalisations, rather than gain them, by identifying a morpheme.

3. The pattern seems to be removal of meaning. In Russian there is a morpheme -sja, called an anticausitive, that apparently subtracts the meaning component ‘cause’ from the meaning of the stem it is attached to. Thus, compare the following two words:

otkryt ‘cause to open’

otkryt’sja ‘open, become open’

Difficulties like these have led morphologists to think of other ways of describing the morphology of languages than the item-arrangement style discussed in Chapter 3. See the Guide to further reading, p.74 for some basic references to alternative ‘word-paradigm’ types of morphology.

3.2 Two other types of affix

In §3.3 we identified three types of affix: prefixes, suffixes and infixes. There are other types as well, two of which we mention here.

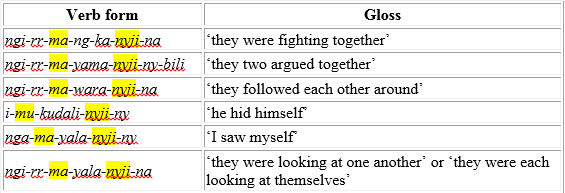

1. Circumfixes. As the name suggests, these go around the root or stem. An example is the morpheme that goes into the Warrwa (Nyulnyulan, Australia) verb to indicate that the action is done to the person themself or among themselves (if there is more than one) — i.e. a morpheme that indicates reflexive (as in I hit myself) or reciprocal (as in We hit one another) meaning. The morpheme is made up of one part ma- (alternating with mu- — can you suggest a conditioning factor?) that goes before the verb root, and a second part -nyji that follows the root. This is illustrated by the following examples:

ngi-rr-ma-yala-nyji-na ‘they were looking at one another’ or ‘they were each looking at themselves’

The two parts of the circumfix ma- ... -nyji are virtually always both present, and meaning is associated with the pair together, rather than to each separately. It is the pair as a unit that is the sign, the morpheme.

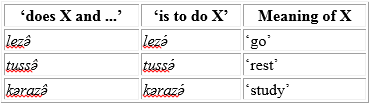

2. Suprafixes or tonemes. These go ‘above’ the word (like prosodies or suprasegmentals in phonetics and phonology). Look at the following verb forms in Kanuri (Nilo-Saharan, Nigeria), where the ̂ diacritc indicates falling tone, the ́high tone.

Here the form of the morpheme meaning ‘does X and ...’ is falling tone on the final vowel, while the form of the morpheme meaning ‘is to do X’ is high tone on the final vowel. Tonemes are found in a number of African languages; whereas case morphemes in languages like Latin (see textbook) are suffixes, in Terik (Nilo-Saharan, Kenya) they are suprafixes.