Are you sure you want to reset the form?

Your mail has been sent successfully

Are you sure you want to remove the alert?

Your session is about to expire! You will be signed out in

Do you wish to stay signed in?

Linguistics: An Introduction > Student Resources > Chapter 9

The tables on this page can be downloaded here:

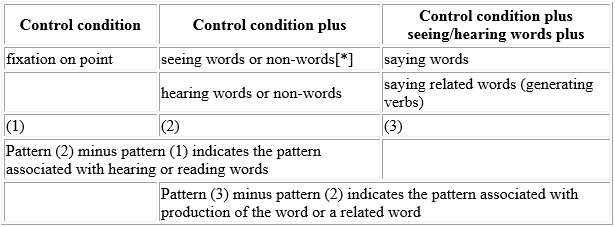

9.1 Subtraction paradigm in brain imaging

The subtraction paradigm is the basic one in PET and fMRI experiments.

Just looking at the pattern of recorded blood flow while the subject is performing an experimental task is not going to tell you a lot about the connection between the cognitive task and blood flow (and hence neural activity). For instance, the pattern of blood flow in the brain on presentation of a spoken word does not necessarily indicate the brain activity specifically associated with hearing a word. Some of the blood flow is likely to be the result of processing the visual signals reaching the brain, and other activities the brain is engaged in.

What can be done in the simple case is to measure the blood flow in a control state. This might be for example be the state of looking fixedly at a cross-hair (+) on a screen in the scanner. If the pattern of blood flow in this condition is subtracted from the pattern of blood flow in the condition of looking fixedly at the cross-hair and simultaneously hearing a spoken word, the resulting blood-flow pattern can be presumed to indicate the blood flow associated with hearing a word. (Even if the subject has their eyes shut during the experiment, we need to take the blood-flow pattern in this state and without hearing a word from the pattern associated with hearing the word.)

The subtraction paradigm thus relies on identifying conditions that are in minimal contrast with one another, where the minimal contrast corresponds to the task to be investigated. Fundamental to this paradigm is the assumption that a cognitive task can be added to another cognitive task without any effect on it. This assumption turns out to be questionable (because of the non-linear nature of brain processes).

In order for experiments of this sort to reveal anything about brain locations associated with particular cognitive tasks the change in blood flow associated with the different conditions must of course be averaged across subjects.

The subtraction paradigm is used in the PET studies referred to in the textbook (pp.220–221). Schematically the design of the experimental conditions in this study is as follows:

[*]: The category of words here included both actual and possible words, while non-words were simple tones and vowel sounds.

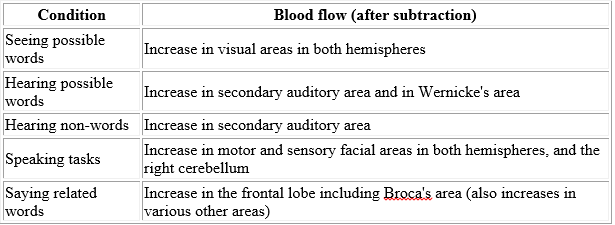

The results of the experiments are summarized below (note this is a partial presentation, and leaves out many complexities):

9.2 Links

Psycholinguistic experiments

The following are links to a selection of websites where you can try for yourself a number of psycholinguistic experiments mentioned in Chapter 9. This is not an exhaustive listing by any means, and you should surf the web for further implementations of these and other experimental paradigms.

McGurk effect

The web contains a large number of illustrations and discussions of the McGurk effect.

YouTube has a good version. Here’s what you do. In this video you will see and hear a person saying some simple syllables. You should watch the person carefully, and listen carefully to what they say. Write down the syllables you hear. Replay the video until you are sure you have written all the syllables down.

Now start the video again and close your eyes while the video is playing. What do you notice?

• Another good McGurk can be found at the Auditory Neuroscience website. (Look for others yourself; there video are some others on YouTube.)

• A basic explanation of the effect can be found on Wikipedia.

Categorical perception

The categorical nature of speech perception is discussed on p.209 of the textbook. You can do experiments in categorical perception online if you have a sound card in your computer, and speakers or headphones (preferably).

• At Haskins laboratory website you will find electronic versions of syllables in the b-d-g continuum (created by modifying formant transitions, which we have not discussed in the textbook). Select “listen to the entire continuum”. What do you notice?

• Anders Eriksson provides another useful set of experiments in categorical perception. These also involve the b-d-g continuum. A good deal of useful information about categorical perception and the interpretation of the results of the experiment is provided after you have completed the experiments.

Dichotic listening task

An interactive online version is available. You will need a sound card and speakers or headphones.

Stroop effect

Question 2 (p.224) asks you to find out about this effect (see e.g. The Stroop effect on Wikipedia). Online versions of the Stroop task can be found at Erik H. Chudler's web site (Neuroscience for Kids) and various other websites (most of which have very short half-lives, which is why no others are mentioned here). Try out the experiment.

Brain images

The Comparative Mammalian Brain Collections contains numerous images of the brains of mammals, including humans. This site contains an enormous amount of information and is well worth exploring.

The homunculus — or “little man inside the head”[*] — provides a visual indication of the area of the cortex concerned with sensory perception or motor control. Various models showing what a man’s body would look like if each part was sized in proportion to the cortical area concerned with the part can be found on the internet by searching for “homunculus”. (Unfortunately, the best examples seem to have disappeared from the internet.)

[*]: I have searched unsuccessfully for examples of female homunculi.