johndoe@gmail.com

Are you sure you want to reset the form?

Your mail has been sent successfully

Are you sure you want to remove the alert?

Your session is about to expire! You will be signed out in

Do you wish to stay signed in?

Please find a PDF copy of this page here.

Name: Koray Çavuşoğlu

Date: 21 January 2024

QUESTIONNAIRE ON DELISTING

Germany

PART I. VOLUNTARY DELISTING

A delisting is deemed voluntary if it is initiated by the company or a shareholder.

1. Is voluntary delisting explicitly allowed by national laws or by jurisprudence?

Yes (X) No

Relevant provision:

• regular delisting: § 39(2) sentence 1 Stock Exchange Act (Börsengesetz; hereafter: BörsG);

• cold delisting: §§ 327a et seq Stock Corporation Act (Aktiengesetz; hereafter: AktG); § 320 AktG; §§ 179a, 262(1) no 2 AktG; §§ 2 et seq Transformation Act (Umwandlungsgesetz; hereafter: UmwG); §§ 191 et seq UmwG

2. If the answer to 1. is yes, who decides so?

BoD (X) GA Other

Relevant provision:

§ 39(2) sentence 1 BörsG, § 76(1) AktG; possibly § 111(4) sentence 2 AktG

According to § 39(2) sentence 1 BörsG, the issuer can apply for delisting. The provision does not specify which organ of the issuer is competent for the application. Nowadays, there is a consensus that, in principle, only the executive board (Vorstand) is competent for the application. Irrespective of this, the supervisory board (Aufsichtsrat) may reserve the decision on delisting for its approval (§ 111(4) sentence 2 AktG – Zustimmungsvorbehalt). Furthermore, there is an ongoing discussion as to whether it is possible to stipulate a requirement for a resolution of the general meeting in the articles of incorporation about the delisting decision of the executive board (1).

In recent years, there has been an ongoing debate about whether shareholders’ approval is necessary for a delisting application. The background of this discussion is the question of whether investor protection should be guaranteed through corporate law or capital markets law. The AktG does not contain any specific regulations on this subject. Initially, the Federal Court (Bundesgerichtshof) ruled that, due to the negative impact of the marketability of the shares, a resolution of the general meeting and an obligatory offer to buy the shares of (dissenting) shareholders is needed (BGHZ 153, 47 – Macroton). However, the Federal Constitutional Court (Bundesverfassungsgericht) ruled a few years later that a voluntary delisting does not affect the scope of protection of the constitutional property guarantee (Article 14 Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany (Grundgesetz; hereafter: GG)) (BVerfGE 132, 99). Subsequently, the Federal Court changed its ruling and stated that a resolution of the general meeting and an obligatory offer to buy the shares of (dissenting) shareholders is no longer needed (BGH NJW 2014, 146 – Frosta). Hence, investor protection was no longer guaranteed through corporate law, and capital markets regulations also failed to provide any form of investor protection. As a result, a significant number of companies went private after Frosta (cf Q 35). This unsatisfactory situation has led to intense discussions about investor protection (2). Numerous voices in literature called the legislator for action to introduce a regime that provides adequate protection of investors. As a consequence, the legislator created a legal framework for investor protection in § 39(2)-(6) BörsG in 2015 (3).

3. What is the quorum requirement for the delisting decision of the competent organ?

The quorum requirement for the delisting decision of the competent organ is based on general rules for executive board decisions. There are no specific rules regarding the delisting decision. Moreover, the German Stock Corporation Act does not contain any specific regulations about quorum requirements for decisions of the executive board. The quorum requirements can be regulated in the rules of procedure (§ 77(2) AktG – Geschäftsordnung). According to the general principles of German corporate law, all members of the executive board must be invited to the meetings of the executive board, stating the subject of the resolution. No minutes needed. Furthermore, there are no requirements for determining the quorum.

4. What is the majority requirement for the delisting decision of the competent organ?

The executive board generally decides unanimously (§ 77(1) sentence 1 AktG). The articles of incorporation or the rules of procedure can stipulate another majority requirement (§ 77(1) sentence 2 AktG). In particular, it is possible to delegate management tasks to individual members of the executive board or to introduce a simple majority of voting rights. However, it is not possible to delegate outstanding management tasks (Leitungsaufgaben) to individual members of the executive board. Decisions regarding delisting can be counted among the outstanding management decisions.

5. Do (minority) shareholders have statutory veto rights as to a delisting decision?

Yes No (X)

6. Should delisting take place within a specific timeframe after the relevant decision? Is there a specific period of time after the decision in which the delisting should be completed?

Yes No (X)

7. Should the delisting application give a full statement of reasons for the submission of such application?

Yes No (X)

Relevant provision:

§ 39(2) sentence 1 BörsG

8. Is it required that a competent authority approves the voluntary delisting?

Yes (X) No

Relevant provision:

§ 39(2) sentence 1 BörsG

If the answer to 8. is yes, who is the competent authority?

The competent authority is the market operator (Börse) itself, as stated in § 2(1) BörsG. The decision to delist is the responsibility of the management of the market operator (§ 39(2) sentence 1 BörsG; Geschäftsführung – § 15(1) sentence 1 BörsG).

If the answer to 8. is yes, does the competent authority has the competence to verify the reasons of delisting?

Yes No (X)

Relevant provision:

§ 39(2) sentence 2-3 BörsG

The competent authority does not have the competence to verify the reasons of delisting, but to verify whether the requirements of § 39(2) sentence 2-3 BörsG have been met.

9. In case of a voluntary delisting does the issuer have to make an offer to buy the shares of (dissenting) shareholders?

Yes (X) No

Relevant provision:

§ 39(2) sentence 3 no 1 BörsG in conjunction with § 31 Securities Acquisition and Takeover Act (Wertpapiererwerbs- und Übernahmegesetz; hereafter: WpÜG)

If the answer to 9 is yes, at what price should the offer be made? How is the price calculated?

The requirements for the price of the offer are subject to a detailed regulation (cf § 39(3) BörsG). The compensation shall be made in monetary payment in euro. Generally, the consideration of the compensation must at least correspond to the weighted average domestic stock exchange price of the securities during the last six months prior to the publication of the offer (§ 39(3) sentence 2 BörsG). The calculation based on the stock market price takes into account that the delisting only affects the tradability of the shares, and not the membership rights of the shareholder.

According to § 39(3) sentences 3-4 BörsG, there are three exception to the price calculation based on stock exchange prices. The first exception applies if the issuer, contrary to Article 17 MAR (Regulation (EU) No 596/2014), does not immediately publish inside information that directly affects that issuer or publishes untrue inside information that directly concerns the issuer in a notification pursuant to Article 17(1) MAR. The second exception applies if the issuer violates the prohibition of market manipulation according to Article 15 MAR. In both cases, the issuer is obliged to pay the difference between the consideration stated in the offer and the consideration corresponding to the value of the company determined on the basis of a valuation of the issuer. The third exception refers to illiquid markets and applies, if the securities of the issuer to which the offer relates have been quoted on less than one third of the trading days during the six months preceding to the publication of the offer and if several successively quoted prices differ from each other by more than five per cent (§ 39(3) sentence 4 BörsG). In this case, the offeror is obliged to pay a consideration which corresponds to the intrinsic value of the company determined on the basis of a valuation of the issuer. The stock exchange prices do not provide an adequate basis in these cases. The intrinsic value of a company is assessed by auditors, which is a time-consuming and costly process. This is one of the reasons why German law primarily refers to stock market prices.

There are ongoing discussions as to whether these exceptions are non-exhaustive (4). The Covid 19 pandemic has shed new light on this debate. The pandemic has shown that the consideration based on the stock market prices can be problematic in some cases, as it does not reflect the true value of the share. Consequently, the question arises as to whether further exceptions to the generally applicable stock exchange price should be considered. As an example, the delisting of Rocket Internet can be mentioned, where the major shareholder initiated a delisting using the falling stock exchange prices caused by the Covid-19 pandemic. One opinion thus advocates an exception to the generally applicable stock exchange price in such cases (5). As a result, investors would be entitled to claim consideration based on the intrinsic value of the company. However, the German legislator currently does not intend to change the existing regulation in this regard.

10. Are there any restrictions due to the principle of maintenance of the share capital?

Yes (X) No

Relevant provision:

§ 57 AktG

In delisting procedures, the general rules of principles of maintenance of the share capital apply. According to § 57(1) sentence 1 AktG the company is not allowed to pay the contributions of the shareholders back. This provision is interpreted narrowly. The principles of maintenance of the share capital are in terms of delisting only relevant in the case that the issuer makes the bid. Nevertheless, in this case, the exception according to § 57(1) sentence 2 AktG will apply (permitted acquisition of own shares). This can be justified by analogy to § 71(1) no 3 AktG (6).

11. Does a (majority) shareholder or a third person has the right to offer to buy the shares of (dissenting/all) shareholders and relieve the issuer?

Yes (X) No

Relevant provision:

§ 39(2) sentence 3 BörsG

That’s the standard case.

12. In case of a voluntary delisting does the issuer or a third person have the obligation to publish a prospectus / informational document?

Yes (X) No

Relevant provision:

§ 39(2) 3 no 1 BörsG in conjunction with §§ 10 et seq WpÜG, § 2 Offer Regulation on the Securities Acquisition And Takeover Act (WpÜG-Angebotsverordnung; hereafter WpÜG-AngVO)

There is no obligation to publish a prospectus in sense of Regulation (EU) 2017/1129. However, the bidder is obliged to publish the so-called offer documents under WpÜG. The offer documents must have been published before the application for delisting is made. The purpose of this requirement is to ensure that the investor has all the necessary information to make an informed decision about the offer (cf § 11(1) sentence 2 WpÜG). § 11(2)-(4) WpüG in conjunction with § 2 WpÜG-AngVO set out the information that must be provided in the offer documents. For example, the offer documents must include the name of the bidder and information on the measures necessary to ensure that the bidder has the resources to fulfil the offer. For further requirements, please check the mentioned provisions.

13. Is an exit opportunity / mechanism that allows investors to exit their investments (e.g. sell – out right) available for shareholders in case of delisting? What are the relevant provisions (please provide translations)?

Yes (X) No

If yes, please define:

In the event of delisting, shareholders can sell their shares to either the bidder of the mandatory offer (§ 39(2) sentence 3 BörsG) or to another third party.

14. Is there any specific provision on downlisting? If not, is downlisting allowed, and how does it take place?

Yes (X) No

A downlisting occurs when the shares are no longer traded on a regulated market (as defined by Union law) but on an MTF.

Downlisting cases are treated like regular delisting cases

15. Is there any specific provision on market migration (delisting from a regulated market and listing in another)?

Yes (X) No

Relevant provision:

§ 39(2) sentence 3 no 2 BörsG

If yes, please define:

The provision states that a delisting is permissible in those cases where the securities are listed in another domestic regulated market or in another members state of the European Union or another contracting state to the agreement on the European Economic Area for trading on an organized market, provided that corresponding conditions apply to a revocation of listing as in § 39(2) sentence 3 no 1 BörsG (obligatory offer to buy the securities). In these cases, the offer to buy the securities of dissenting shareholders is not mandatory.

16. Is there any specific provision on voluntary delisting in case of increase of listing requirements by both the Law and Stock Exchange?

Yes No (X)

17. Are there different rules on delisting for national and foreign listed companies?

Yes No (X)

Relevant provision:

§ 39(4) BörsG

18. Cold delisting is usually described as a transformation of a listed company resulting to its delisting, including especially the merger by absorption of a listed company by an unlisted company. What is defined as cold delisting in your legal order? Is there any specific provision on cold delisting?

Although there is no legal definition of cold delisting, one can understand under cold delisting all restructuring measures under corporate or transformation law which leads to the fact that the securities of the corporation can no longer be traded on stock exchanges or comparable organized markets. There is no specific provision on cold delisting. The applicable provisions depend on the specific restructuring measure.

19. Does the merger of a listed company with a non-listed company lead to delisting? Is an exit opportunity available for shareholders? What are the relevant provisions? (please provide translations)

Yes (X) No

Relevant provision:

§ 20(1) no 2 UmwG in conjunction with § 43(2) Administrative Procedure Act (Verwaltung-sverfahrensgesetz; hereafter: VwVfG); §§ 29(1), 33 UmwG

A merger involving a listed company and a non-listed company results in delisting if the acquiring legal entity is not listed or cannot be listed on the stock exchange at all. However, if the acquiring legal entity is the listed company and the transferring legal entity is the non-listed company, the listing of the listed company will not be affected.

According to § 29(1) UmwG, the acquiring legal entity must offer to each shareholder who objects to the merger resolution adopted by the legal entity being acquired the option to sell their shares or memberships in exchange for appropriate cash compensation. Therefore, one exit option for shareholders is to sell their shares to the acquiring legal entity in return for suitable cash compensation. Additionally, shareholders have the option to sell their shares to third parties. As per § 33 UmwG, any restrictions in place with the involved legal entities regarding dispositions do not prevent shareholders from disposing of their shares in any other way once the merger resolution has been adopted. This remains applicable until the period stipulated in section 31 has lapsed.

20. Does the successful completion of a mandatory bid give the right to delisting? If yes, are there any preconditions?

Yes (X) No

Relevant provision:

§ 39(2) sentence 3 No. 1 BörsG

If yes, please define:

There are no other preconditions than the completion of the mandatory bid. § 39 BörsG focuses on the protection of the investor’s financial assets. Therefore, a mandatory bid as the only precondition suffices.

21. Are there specific rules on delisting from an MTF?

There are no specific rules governing delisting from an MTF. The regulations concerning delisting from a regulated market (§ 39 BörsG) do not extend to the delisting process from an MTF (7).

PART II. OBLIGATORY DELISTING

A delisting is deemed compulsory/obligatory, if it is initiated by a supervisory authority or a market operator without consent of the company.

22. What are the prerequisites for compulsory delisting by the competent national supervisory authority?

The Management Board of the market operator may revoke the admission of securities to trading on the Regulated Market, except in accordance with the provisions of the VwVfG, if orderly exchange trading is no longer guaranteed in the long term and the Management of the market operator has discontinued the listing on the Regulated Market or the issuer fails to fulfil its obligations under the admission even after a reasonable period of time (§ 39(1) BörsG). The executive board has discretion over this decision.

23. Which body has been designated as the competent authority, in particular regarding the power to require the removal of a financial instrument from trading pursuant to art. 69(2)(n) MiFID II?

According to § 3(1) BörsG compliance with the provisions of the BörsG by the market operator is monitored by the competent supreme state authority (oberste Landesbehörde) (ex-change supervisory authority; Börsenaufsichtsbehörde). Supervision shall extend to compliance with the provisions and directives under exchange law, the orderly conduct of trading on the exchange and the orderly fulfilment of exchange transactions (settlement of ex-change transactions; Börsengeschäftsabwicklung). The Federal Financial Supervisory Authority (Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht; hereafter BaFin) has no competences in this area.

The competent authority, as outlined in § 2(1) BörsG, is the market operator (Börse). The market operator possesses the authority to remove financial instruments from trading in accordance with §§ 25(1) and 39(1) BörsG.

Pursuant to § 3(1) BörsG, the market operator's adherence to the provisions of the BörsG is overseen by the competent supreme state authority (oberste Landesbehörde), also known as the exchange supervisory authority (Börsenaufsichtsbehörde). This oversight encompasses compliance with the regulations and directives under exchange law, the orderly conduct of trading on the exchange, and the proper fulfillment of exchange transactions (settlement of exchange transactions; Börsengeschäftsabwicklung). It's important to note that the BaFin does not have competences in this specific area.

24. What are the rules of the market that can justify a compulsory delisting imposed by market (art. 52 MiFID II)?

The market operator can justify a compulsory delisting according to § 39(1) BörsG, if orderly exchange trading is no longer guaranteed in the long term and the Management of the market operator has discontinued the listing on the Regulated Market according to § 25(1) sentence 1 no 2 BörsG. Insolvency of the issuer is a conceivable case which justifies the assumption that stock exchange trading is no longer guaranteed in the long term. Illiquidity or a squeeze out decision are not such cases. According to the literature, the provision must be interpreted narrowly due to the substantial impact on the issuer.

25. Have any of the voluntary or obligatory delisting requirements above changed materially since 2010 (e.g., due to a legal decision or amendment of the regulations)?

Yes, please check the answer to Q 2.

PART III. GENERAL QUESTIONS (if not already answered)

26. How are dissenting shareholders protected in voluntary delisting?

a. Regular delisting

Dissenting shareholders can take legal action against the bidder of the offer, seeking payment of an appropriate consideration as outlined in § 39(3) sentence 2-4 BörsG in conjunction with § 31 WpÜG (8). The question of whether individual investors have a right of action against the market operator’s decision to delist a company is subject to dispute in the literature (9). The prevailing view is that individual investors have a right of action against the revocation decision of the market operator (cf. T Eckhold, ‘Delisting’ in R Marsch-Barner and F Schäfer (eds), Handbuch börsennotierte AG, 5th edn (Cologne, Otto Schmidt, 2022), Delisting, para. 63-69 et seq.). However, in administrative court proceedings, the adequacy of the consideration cannot be reviewed (§ 39(6) BörsG), thus rendering this procedure not very relevant in practice.

b. Cold delisting

Firstly, the shareholders are protected by the fact that the decision for a cold delisting requires a resolution of the general meeting with a qualified majority (§§ 13, 65, 125, 193 UmwG; § 179a(1) AktG, § 320 AktG; simple majority: § 327a(1) AktG;). Secondly, the share-holders must be given the opportunity to exit the company in return for cash compensation (§§ 29, 125, 207 UmwG; § 327b AktG), calculated on the basis of the true value of the shares (10). In the case of a cold delisting in accordance to § 320 AktG (Integration by a resolution of the majority), a cash compensation offer is required only when the principal company is a controlled company (cf § 320(2) sentence 1 no 2 AktG, § 320b(1) sentence 3 AktG). In other cases, the future principal company is only obliged to offer their own shares to the leaving stockholder. This can be unsatisfying as the cold delisting limits the tradability of the share. Nevertheless, the literature does not advocate an analogy to cash compensation (11).

27. What are the sanctions in case of a breach of the delisting rules?

There are no legal sanctions in case of a breach of delisting rules.

28. Is there a special duty of loyalty (for the board or, if applicable, the shareholders) imposing further restrictions in connection with a delisting?

There is no special duty of loyalty for the board.

29. How are shareholders protected in obligatory delisting?

The shareholders can take legal action against the market operators revocation decision (see Q 26). Furthermore, there is an ongoing debate whether investors are entitled to file an administrative liability claim. The majority opinion on this matter is that such a claim is not permissible, as the executive board of the market operator is only acting in the public interest and not for the benefit of third parties (12).

30. Have shareholders successfully challenged delisting decisions in the past? If Yes, could you provide any names of cases?

Since the implementation of the new delisting regulations in Germany (see answer to Q 2), there have been no known court decisions in which shareholders were able to successfully challenge the delisting decision in court.

31. How is the issuer protected in (obligatory) delisting?

The issuer may take legal action against the revocation decision of the market operator. Additionally, the issuer may sue for damages against the competent bodies of the company. Moreover, the issuer may have an administrative liability claim against the market operator, since the administrative duty exists precisely towards the issuer. As such, this case differs from the action of the individual shareholders (see Q 29).

32. How does insolvency and restructuring of a listed company affects delisting? Specifically: a) Does the initiation of formal insolvency (liquidation) procedures automatically trigger mandatory delisting? b) Does the initiation of formal restructuring / reorganization procedures automatically trigger mandatory delisting? c) If the above scenarios do not automatically trigger mandatory delisting, what else are the implications? d) Please give empirical information (if available) on the treatment of insolvent listed firms by trading venues in your jurisdiction e) What are the relevant provisions (please provide translations)?

Voluntary Delisting

Insolvency and restructuring of a listed company do not have any legal effect on delisting procedures. In cases of third-party administration (Fremdverwaltung), it is the responsibility of the insolvency administrator to submit the application for delisting (§ 80(1) Insolvency Code (Insolvenzordnung; hereafter: InsO). § 39 BörsG does not provide any specific rule for these cases. Delisting of an insolvent company is usually not feasible, as the mandatory offer requirement cannot be met. No one will voluntarily make a mandatory offer for an insolvent company. Therefore, according to the literature, the legislator should consider reducing the level of protection for shareholders in favor of the creditors of the insolvent issuer in such cases (13).

Obligatory Delisting

Obligatory delisting can occur in two cases (§ 39(1) BörsG): (1) if orderly stock exchange trading cannot be guaranteed in the long term and the management of the market operator has discontinued the listing on the regulated market, or (2) the issuer fails to fulfill its obligations arising from admission even after a reasonable period of time.

(1) According to literature and market operator practices, the mere application for insolvency () and the initiation of insolvency proceedings (Insolvenzeröffnung) are not sufficient to assume a permanent failure to ensure orderly stock exchange trading (14). Additional circumstances are required, such as the company's cancellation, rejection of the insolvency application due to lack of assets, or the final distribution of the AG's assets in insolvency proceedings.

(2) The initiation of formal insolvency procedures does not automatically trigger obligatory delisting under § 39(1) BörsG. In this case, the insolvency administrator (Insolvenzverwalter) is expected to assist the issuer in fulfilling obligations under this Act, particularly by providing necessary funds from the insolvency estate (Insolvenzmasse) in accordance with § 43(1) BörsG. According to literature, in certain cases, the initiation of insolvency proceedings may be a reason for the suspension of trading and the revocation of admission if the insolvency estate is clearly insufficient for fulfilling the issuer's obligations under § 39 BörsG (15).

Empirical data

No empirical data are available on the treatment of insolvent listed firms by trading venues in Germany. Nevertheless, there are famous examples of companies that were insolvent and still listed, such as Wirecard AG, Philipp Holzmann AG, or Air Berlin PLC.

Relevant Provisions

§ 39(1) BörsG: The Management Board of the market operator may revoke the admission of securities to trading on the Regulated Market, except in accordance with the provisions of the VwVfG, if orderly exchange trading is no longer guaranteed in the long term, and the Management Board of the market operator has discontinued the listing on the Regulated Market, or the issuer fails to fulfill its obligations arising from admission even after a reasonable period of time.

§ 43(1) BörsG: If insolvency proceedings are opened concerning the assets of a person obliged to act under this Act, the insolvency administrator shall support the debtor in fulfilling obligations under this Act, particularly by providing necessary funds from the insolvency estate.

33. Do relevant courts have the power to examine the delisting reasοns on the merits?

The relevant courts have the power to examine the delisting reasons only in cases of obligatory delisting.

34. What are the legal consequences of delisting: a) on shares, b) on shareholders, c) on the issuer?

a) The main consequence of delisting on shares is that the shares can no longer be traded on a regulated market, although they can still be traded on a MTF (Freiverkehr) in accordance with § 48 BörsG. The necessity for the issuer's consent regarding the inclusion of shares in the MFT is contingent upon the general terms and conditions stipulated by the respective stock exchange. Generally, the issuer’s consent is not required (16). However, some stock exchanges do require the issuer's consent (§ 9(2) AGB-Freiverkehr Börse München).

c) The Stock Corporation Act (AktG) and other corresponding legislation, such as the commercial code (HGB), contain specific rules for listed companies. After delisting these provisions no longer apply, which has a deregulatory effect on the company. The MAR rules also apply to issuers whose shares are only traded on a MTF (Article 2(1)(b) MAR). Though, the regulation of public disclosure of inside information only applies if the issuer has approved trading of their financial instruments on an MTF (Article 17(1) MAR).

b) Still to be mentioned, there are no specific legal consequences of delisting on share-holders. Hence, they can maintain their share regardless of the obligatory offer and can make use of their membership rights.

35. Are there any statistical data on delisting in your Country? If yes, please provide further details. Are there any statistical data, or evidence, on downlisting in your Country? If yes, please provide further details. Are there any statistical data, or evidence, on delisting from an MTF in your Country? If yes, please provide further details.

a) Bibliography

Markus Doumet, Peter Limbach and Erik Theissen, Ich bin dann mal weg, 2015, available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2660074; Ludwig Pilsl, Leonhard Knoll, Delisting und Börsenkurs, DB 2016, 181-186; Christian Aders, Dennis Muxfeld, Felix Lill, Die Delisting-Neuregelung und die Frage nach dem Wert der Börsennotierung, CF 2015, 389-399; Cordula Heldt, Claudia Royé, Das Delisting-Urteil des BVerfG aus kapitalmarktrechtlicher Perspektive, Empirie und Fragestellungen für den Gesetzgeber, AG 2012, 660-673; Grant Thornton, im Auftrag der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, vertreten durch das Bundesministerium für Finanzen, zur Frage: „Bietet die regelmäßige Anknüpfung von Delisting-Angeboten an den 6-Monats-Durchschnittskurs einen angemesse-nen Schutz für Anleger?“, 2022, available at: https://www.grantthornton.de/presse/delisting-gutachten-fuer-bmf-2022/; Behzad Karami, René Schuster, Eine empirische Analyse des Kurs- und Liquiditätseffekts auf die Ankündigung eines Börsenrückzugs am deutschen Kapitalmarkt im Lichte der „FRoSTA“-Entscheidung des BGH, Working Paper 2015; Marc Berninger, Dirk Schiereck, Dominik van de Vathorst, Der Abfindungsanspruch beim Rückzug aus dem regulierten Markt – eine empirische Evaluation der gesetzlichen Neuregelung, ZBB 2019, 329; Florian Eisele, Andreas Walter, Motive für den Rückzug von der Börse – Ergebnisse einer Befragung deutscher Going Private- Unternehmen, 2006, ZfbF, 807-833; Eisele Florian, Walter Andreas, Kursreaktionen auf die Ankündigung von Going Private-Transaktionen am deutschen Kapitalmarkt, 2006, ZfbF, 337-362; Weimann Martin, Ertragswert und Börsenwert, Empirische Daten zur Preisfindung beim Delisting, 1. Auflage, 2020; Wessels Ulrich, Röder Klaus, Die Kursentwicklung von Delistings in Deutschland, Corporate Finance, 2016, 357; Wolfgang Bessler, Johannes Beyenbach, Marc Stefen Rapp, Marco Vendrasco, Why do firms downlist or exit from securities markets?, Evidence from the German Stock Exchange, Review of Managerial Science ,2023, 1175–1211.

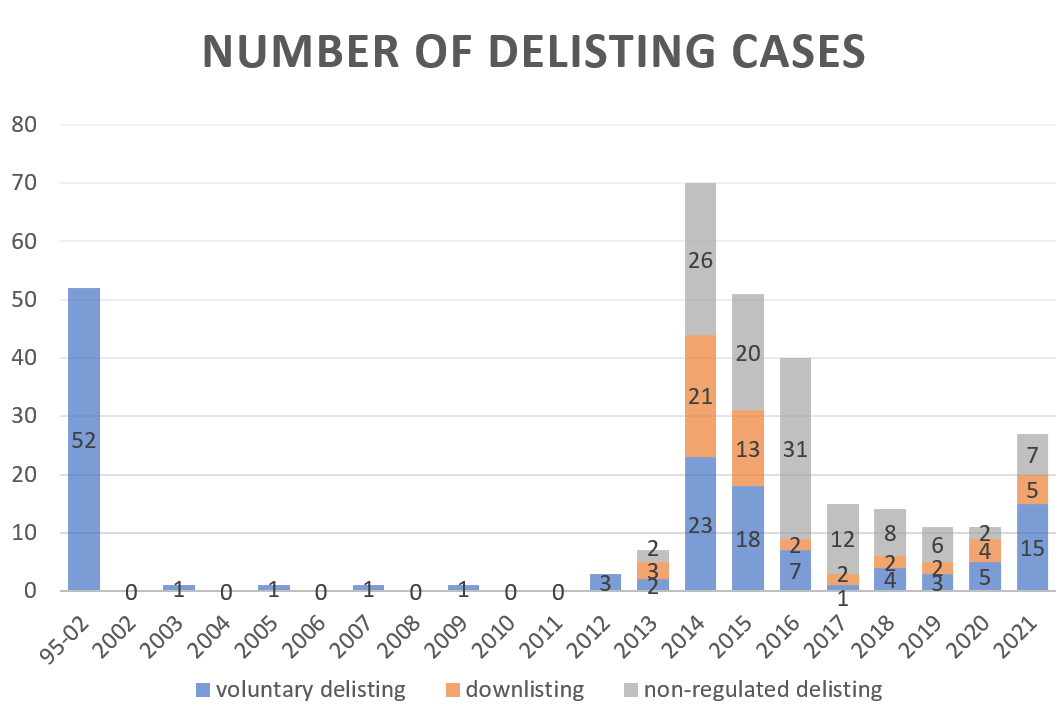

b) Number of delisting cases

The aim of this section is to demonstrate the number of delisting cases over a period of time from 1995 to 2021. The chart presented illustrates the cases of voluntary delisting from regulated markets, non-regulated delisting (delisting from non-regulated markets; § 39 BörsG does not apply in this case) or downlisting cases (downlisting from regulated to non-regulated markets). The data for the chart is sourced from Eisele/Walter (ZfbF, 2006, 337) for the years 1995-2002; from Wessels/Röder (2016) for the years 2002-2012; from Grant Thornton (2022) for the years 2013-2021.

Just keep in mind that the Federal Court’s decision in the Macroton case dates back to 2002. This decision stipulated that a resolution of the general meeting and an obligatory offer to buy the shares of (dissenting) shareholders were necessary. However, the Federal Constitutional Court’s decision dates back to 2012, ruling that a regular delisting does not affect the scope of protection of the constitutional property guarantee. As a result, the Federal Court revised its ruling in 2013 in the Frosta case, stating that a resolution of the general meeting and an obligatory offer to buy the shares of (dissenting) shareholders is no longer required. Since November 2015, the amended § 39 BörsG applies in cases of regular delisting and downlisting, which no longer requires a resolution of the general meeting but does mandate a settlement offer.

Figure 1: Number of Delisting Cases

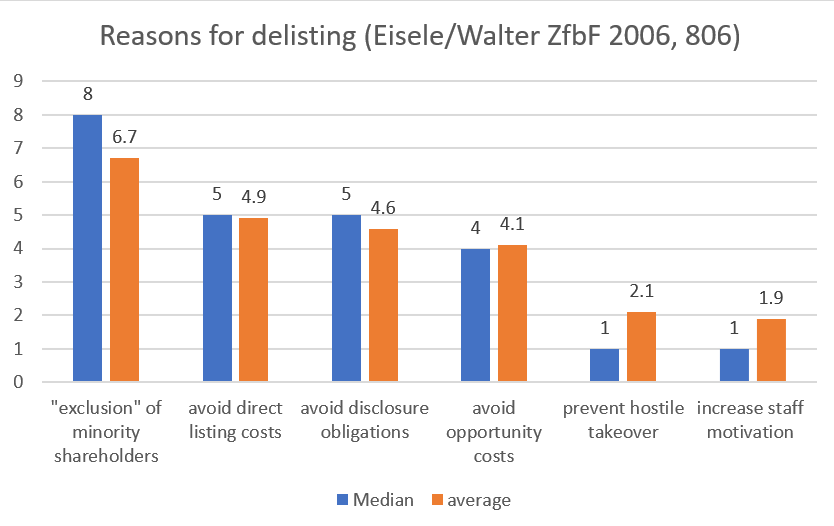

c) Reasons for delisting

The literature also provides some empirical evidence about the reasons of delisting. Eisele/Walter (ZfbF 2006, 806) conducted a study in which they analysed the reasons for delisting by means of a questionnaire. Participants were asked to rate the importance of the given motive for the delisting decision on a scale of 1 (does not matter at all) to 10 (plays an important role).

Figure 2: Reasons for Delisting (Eisele/Walter ZfbF 2006, 806)

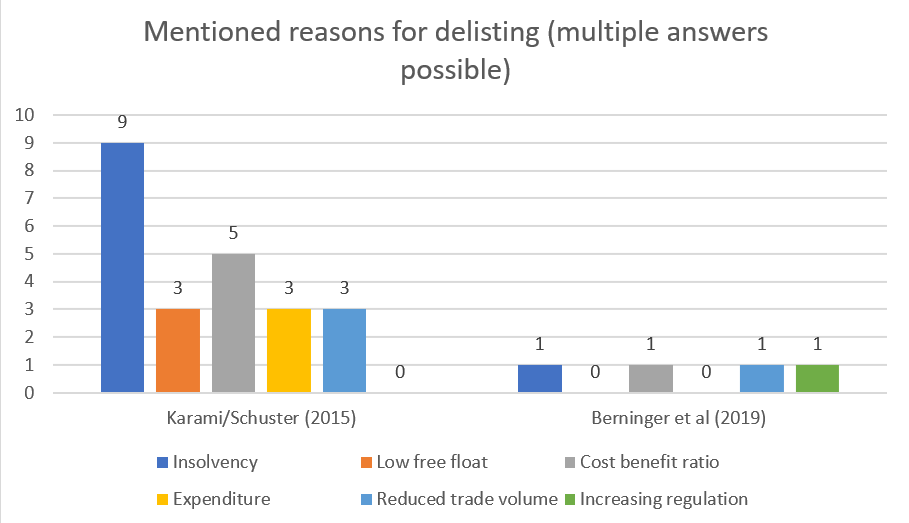

The recent literature differentiates between cases of voluntary delisting, downlisting and non-regulated delisting. The results are illustrated in the following charts.

(1) Voluntary delisting

Figure 3: Mentioned Reasons for Delisting (multiple answers possible)

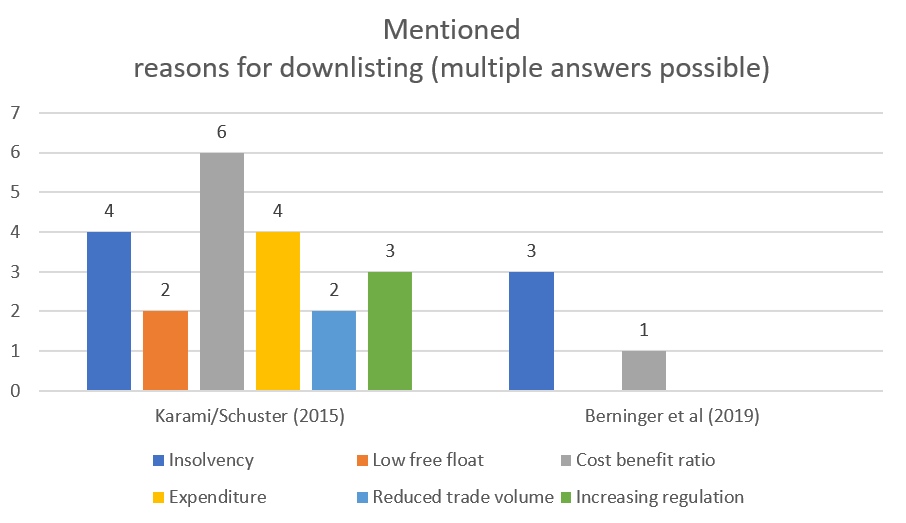

(2) Downlisting

Figure 4: Mentioned reasons for downlisting (multiple answers possible)

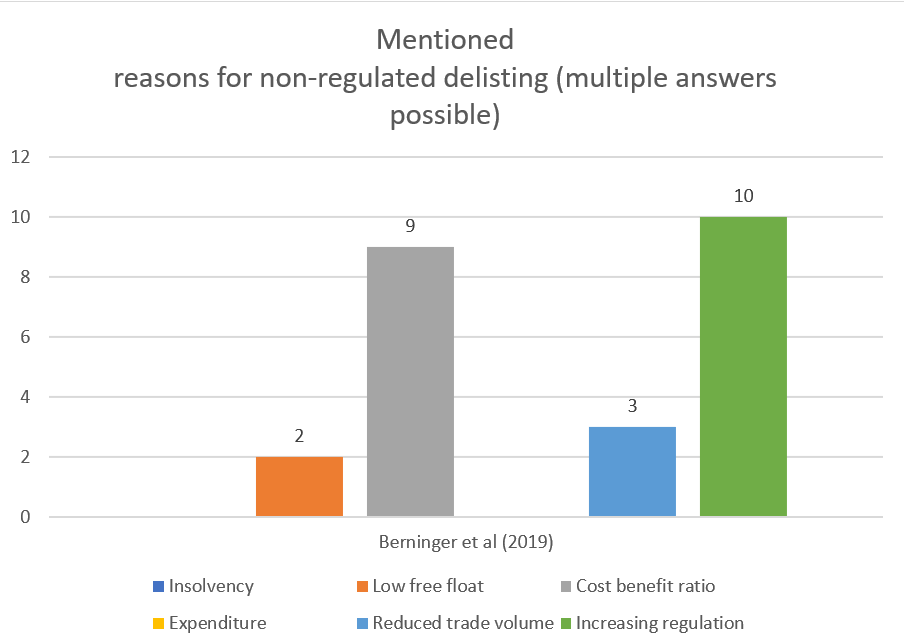

(3) Non-regulated delisting (delisting from non-regulated markets)

Figure 5: Mentioned reasons for non-regulated delisting (multiple answers possible)

d) Price reaction on delisting

Researchers aim to investigate the impact of delisting on the value of shares by analysing the price reaction to delisting announcements. This is done by utilizing the Average Ab-normal Return (AAR) criterion, which expresses the average of the individual abnormal returns of the examined cases. If AAR is not zero, it can be proven that the price reaction is significantly statistically related to the announcement of delisting. In order to analyse whether the AAR in the period around the announcement date is different from zero, it is common to aggregate them temporally in an event window. The reason for this is that, on the one hand, market participants may anticipate the event in the days before the announcement. On the other hand, this temporal aggregation can be used to analyse the speed of adjustment of the stock market price to the new information. For this purpose, the average abnormal return is summed up over several days (so-called cumulative average abnormal return (CAAR)). The following illustration of the results differentiates between voluntary delisting from regulated markets, downlisting from regulated markets to non-regulated markets and delisting from non-regulated markets. Additionally, the results will be classified in a chronological context of the most important legal changes over time.

aa) Voluntary delisting

The oldest available empirical study about price reactions on delisting is written by Eisele/Walter (ZfbF 2006, 337). They examined a sample of 37 delisting cases from 1995 to 2002, up until the Macroton judgment of the Federal Court in 2002. Their event study shows that the capital market reacts to a delisting announcement with sharply rising share prices. They observed an AAR of 10.12 per cent and a CAAR of 24,8. This suggests that the value of shares increased with the announcement of delisting.

The empirical studies following the Macroton decision of the federal court are related to the period from 2003 to 2013. Wessels/Röder (2016) examined delisting cases from this period and observed a significant AAR of 6,57 per cent and a CAAR of 6,42 per cent (-/+ 1 day) but a CAAR of -6,43 per cent (-/+ 4 day). The positive AAR of the announcements in this period is only meaningful to a limited extent. There is no significant positive CAAR over the entire event period, and a piecemeal view of the event period even reveals significantly negative abnormal price effects. Therefore, the positive price reaction upon publication of the ad hoc announcement is relativized to a certain extent.

In 2013, the federal court once again decided over delisting cases in its Frosta decision. The Frosta principles applied until the amendment of § 39 BörsG in November 2015.

Wessels/Röder (2016) examined delisting post-Frosta cases, finding a significant AAR of -9,66 per cent and a CAAR (-/+4 days) of -12,34 per cent. This can be interpreted as a clear disadvantage for the (dissenting) shareholders, since the value of the share has fallen sig-nificantly after the announcement. One reason for this could be the lack of an obligation to make a compensation offer. Similar results were found by Doumet et al (2015) who examined cases from 2013 to 2015, observing an AAR of -3,88 per cent and a significant negative CAAR was observed. Pilsl/Knoll (DB 2016, 181) studied voluntary delisting cases from 2013 till 2015, finding an AAR of -10,10 per cent and a CAAR (+/- 3 days) of -12,69 per cent. Karami/Cserna et al. (2015) studied voluntary delisting cases from 2013 to 2015, finding an AAR of -5,42 per cent. However, their results in connection with CAAR were not significant. Aders et al (CF 2015, 389) also found a negative CAAR when examining delisting cases from 2013 to 2015, with an AAR of -9,4 per cent and a negative CAAR. The authors pointed out, however, that due to the illiquidity of the market a sale of the share for market price was not possible already before the announcement of delisting. The delisting announcement had therefore no impact on the tradability of the shares. The most recent empirical study by Grant Thornton (2022) showed that announcements of delisting led to statistically significant negative abnormal returns of -6,33 per cent, i.e. to a loss of wealth of the share-holders. In conclusion, it can be said that the empirical results demonstrate the negative impact of the Frosta decision on the share value of the shareholders.

After the Frosta decision, § 39 BörsG was amended in November 2015. For the period of time after the amendment in 2015, Berninger et al (ZBB 2019, 329) examined 32 cases up to 2018. In these cases, an AAR of 1,84 per cent and a CAAR of 1,09 per cent were observed. Nevertheless, the results are not statistically representative due to the small sample size. The broader study by Grant Thornton (2022) suggests that the abnormal returns are smaller and sometimes even positive, though it cannot be statistically proven to be different from zero. Consequently, a wealth loss of the shareholders, as observed before the amendment of § 39 BörsG, can no longer be empirically proven. In this respect, the amendment of § 39 BörsG has improved the protection of investors.

bb) Downlisting

Empirical studies concerning downlisting cases have only been available since the Frosta decision in 2013. Doumet et al (2015) did not find a statistically significant price reaction in downlisting cases. Similar results were found by Pilsl/Knoll (DB 2016, 181), who observed an AAR of 0,38 per cent and a CAAR of -0,97 per cent, which were also not statistically significant. Karami/Cserna et al. (2015) had similar results that were not statistically significant. Berninger et al (ZBB 2019, 329) examined 32 downlisting cases from 2015 to 2018 and found an AAR of 2,35 per cent and a CAAR of 9,71 per cent. Nevertheless, the results are not statistically representative due to the small number of cases examined. Grant Thornton (2022) conducted a broader study of downlisting cases from 2013 to 2021. They summarize that announcements of a downlisting do not lead to statistically significant negative abnormal returns, regardless of the regulatory environment in which the downlisting takes place. Rather, the results indicate that after the amendment of § 39 BörsG on the day of the announcement, a statistically significant positive abnormal return is achieved on average. However, the finding that the cumulative abnormal returns are not significantly different from zero shows that this effect is only shortterm in nature. As a result, a wealth loss of the shareholders following the announcement of a downlisting cannot be empirically proven.

cc) Non-regulated delisting (delisting from non-regulated markets)

Non-regulated delistings do not fall within the scope of § 39 BörsG. All available studies observe significantly negative AAR and CAAR. Pilsl/Knoll (DB 2016, 181) recorded a negative AAR of -7,53 per cent and a CAAR (+/- 3 days) of -14,49 per cent. Similarly, Karami/Cserna et al. (2015) observed an AAR of -8,47 per cent and a CAAR of -14,65 per cent. Berninger et al (ZBB 2019, 329) reported a negative AAR of -2,82 per cent and a CAAR of -12,73 per cent. However, the results from Berninger et al are not statistically representative due to the small number of cases examined. All results are in accordance with the broader study of Grant Thornton (2022). According to this study delisting announcement from a non-regulated market is accompanied by statistically significant negative abnormal returns and a loss of shareholder wealth. Explicitly the study showed from an AAR rate of -5,04 per cent respectively -3,04 per cent. The results also show a statistically significant negative CAAR. Therefore, it can be inferred from the empirical studies that delisting decisions from non-regulated markets have a negative impact on share value. This can be attributed to the lack of an obligation to submit an offer in accordance to § 39 BörsG, due to the non-applicability of the law in this case.

36. More specifically, how many cases of voluntary delisting and / or obligatory delisting by the competent national supervisory authority have there been since MiFID I entered into force in 2007? Please also provide the main reasons for mandatory delistings, if available.

See answers to Q 35. There are no statistical data about obligatory delisting and about the main reasons for mandatory delisting.

___________________________

(1)T Eckhold, ‘Delisting‘ in R Marsch-Barner and F Schäfer (eds), Handbuch börsennotierte AG, 5th edn (Cologne, Otto Schmidt, 2022) para 63-61.

(2) W Bayer, ‘Die Delisting-Entscheidungen „Macrotron“ und „Frosta“ des II. Zivilsenats des BGH’ (2015) 1 Zeitschrift für die gesamte Privatrechtswissenschaft 163.

(3) cf explanatory memorandum, BT-Drucks. 18/6220 p 84.

(4) cf M Habersack, ‘Delisting’ in M Habersack, P Mülbert and M Schlitt (eds), Unternehmensfinanzierung am Kapitalmarkt, 4th edn (Cologne, Otto Schmidt, 2019) para 40-24; G Bachmann, ‘Rocket Internet – Ein Fall für den Gesetzgeber?’ (2021) 24 Neue Zeitschrift für Gesellschaftsrecht 609; J Koch, ‘Delisting zu Schleuderpreisen’ (2021) 66 Die Aktiengesellschaft 249.

(5) Koch, ‘Delisting zu Schleuderpreisen’ (n 4).

(6) Cf J Oechsler, ‘§ 71 AktG’ in W Goette, M Haberack and S Kalss (eds), Münchner Kommentar zum Aktiengesetz, 5th edn (Munich, C.H.Beck, 2019) para 171; H Merkt, ‘§ 71 AktG’ in H Hirte, P Mülbert, M Roth, K Hopt and H Wiedemann (eds), Großkommentar AktG (Berlin/Boston, De Gruyter, 2018) para 215.

(7) E Schwark, ‘§ 48 BörsG’ in E Schwark and D Zimmer (eds), Kapitalmarktrechts-Kommentar, 5th edn (Munich, C.H.Beck, 2020) para 28.

(8) BT-Drucks. 18/6220 (n 3) 86.

(9) cf Eckhold, ‘Delisting’ (n 1) paras 63-68 et seq.

(10) cf G Zeidler, ‘§ 30 UmwG’ in J Semler, A Stengel and N Leonard, Beck´sche Kurz-Kommentare, Umwandlungsgesetz, 5th edn (Munich, C. H. Beck, 2021) paras 4 et seq.

(11) H Grigoleit and M Zellner, ‘§ 320b AktG’ in H Grigoleit, Aktiengesetz, 2nd edn (Munich, C. H. Beck, 2020) para 3.

(12) cf § 15(8) BörsG; Eckhold (n 1) para 63-77.

(13) J Häller, ‘Delisting von Aktien in der Insolvenz’ (2016) 36 Zeitschrift für Wirtschaftsrecht 1903, 1910.

(14) T Heidel, ‘Insolvenz und Delisting’ (2021) 21 Zeitschrift für Bank- und Kapitalmarktrecht, 530, 531 et seq.

(15) ibid.

(16) W Groß, ‘§ 48 BörsG’ in W Groß (ed), Kapitalmarktrecht, 8th edn (Munich, C.H.Beck, 2022) para 9; C Kumpan, ‘§ 48 BörsG’ in K Hopt, Handelsgesetzbuch, 41th edn (Munich, C.H. Beck, 2022) para 6; § 7(5) AGB-Freiverkehr Börse Hamburg; § 8(2) AGB-Freiverkehr Börse Frankfurt.